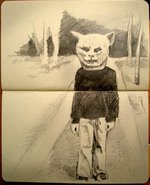

Brothers Myshkin & Raskolnikov

My review of THE IDIOT. Read it for my bookclub.

Written immediately after CRIME AND PUNISHMENT, Dostoevsky gives us THE IDIOT, whose hero, Prince Myshkin, is gentle and Christ-like - the polar opposite of Raskolnikov, the nihilist murderer. Taken together, the two novels give us a fascinating critique of Russian (and Western) society from the perspective of a sinner and a saint, and of a society that has produced both.

Admittedly, THE IDIOT must be seen a minor novel in comparison to CRIME AND PUNISHMENT. It lacks its psychological power and narrative drive. But I would suggest that the greatness of CRIME AND PUNISHMENT is enhanced by reading THE IDIOT. Further, I would argue that much of what is seen to be the greatness of CRIME AND PUNISHMENT originates in the location of the narrator's point of view inside the teeming and tortured mind of the ultimate outsider, Raskolnikov. The third person narrator inside a single consciousness became the "default" practice in the late 19th and early 20th century. This is perhaps why the story of Prince Myskin, our gentle insurgent in THE IDOT who is nearly always seen inside of a Russian society, and whose story is told in a mix of omniscient narrator and from Myshkin's point of view is seen to be old-fashioned or hard to read.

I would argue that given the nature of the story Dostoyevsky is telling here - of a society that cannot cope with an honest and compassionate man that the omniscient narrator's voice is warranted and appropriate (unlike a number of reviewers below for whom this technique comes off as creaky and plodding). To tell the story he wants to tell, Dostoyevsky must move from one drawing room to another, one set of eyewitnesses, gossips, and minor characters to another. These set pieces - such as Natasya's "party" where she chooses whom she will marry, or the nihilist Ipollit's reading of his Confession, also locate THE IDIOT more in the realm of traditional 19th century novel of manners than CRIME AND PUNISHMENT. And its ostensible subject matter - marriage - places it squarely in the genre.

I find it sad that the set pieces in THE IDIOT can seem interminable to some modern readers. Yes, characters do hold forth for pages and pages, propounding theories, relating anecdotes in excruciating detail. In the society of the 19th century, even in the chaotic society of post-feudal Russia where the social order was in flux, the conversational customs of a court society still held sway. Even in the considerably more democratic United States, the presence of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. at social functions was highly prized by elites because he was universally recognized for his acumen as a speaker and conversationalist. These days we don't talk anywhere near as intelligently, as passionately or grandly these marvelous characters, and our suburbanized circumstances reduce our chances for unsettling social encounters as well. Which do you more often attend - parties featuring a stew of anarchic social criticism, bizarre personal attacks and grotesque dissembling, or a dull pudding of sitcom japes and bumpersticker politics? Which would you prefer?

Dostoyevsky fills his drawing rooms with challenges to the status quo, with intemperate invective, with radical claims on the political and economic system. At the same time he gives voice to conservative views, e.g., that Russia was better before Alexander II freed the serfs (in 1861, only 6 years prior to the publication of THE IDIOT), better before the aristocracy began to rub shoulders with powerful merchants and usurers, better before the atheists, nihilists and anarchists attacked the church and the social structure.

Interestingly, many of these contretemps are, as in so much 19th Century fiction, posed in connection with "the woman question." Our heroine, Natasya, raised by her guardian and seduced at a young age. is intent upon exposing Russian society for its hypocritical attitudes and brutal behavior toward women. Brilliant and beautiful, Natasya concoct a series of circumstances that both outrage and shame conventional society. She is the demonic critic of Russian society, her vindictive spirit contrasting sharply with Prince Myshkin's penchant for compassion and forgiveness. Together they form a unique double-edged critique of the bourgeoisie. And both are broken by their society's cruel intolerance and vast hypocrisy.

Prince Myshkin's conversation marks him among members of his society an "idiot" because he speaks forthrightly and answers truthfully without regard for the consequences. So disturbing is this behavior that Aglaya, the woman he hopes to marry, tells him not speak at the gathering at which he is being introduced to high society as a suitor. But driven by the onset of an epileptic fit, he disobeys and gives himself up to a remarkable speech in which his praise for the assembled company, his views on politics and religion are interpreted by most as an insult, and by many as the ravings of a madman. His speech is a form of social suicide, self-murder, and as such the flip side of Raskolnikov's homicide.

In the largest sense, what's at stake in these conversations and disputes is no less than the soul of Russia. Through the prince's speech Dostoyevsky poses the question as to whether Russia will reawaken to her deep and unique Christian heritage and behave, like the prince, with virtue, compassion and honor, or become like the empires to the West whose money-grubbing ways have begun to infect Russia and her people.

THE IDIOT has flaws. There is too much disquisition and exposition even for a 19th century novel. Sometimes, Dostoyevsky will vamp along for a few pages, trying to figure out what to do next. But still, THE IDIOT is well worth reading by itself, or even better, in combination with CRIME AND PUNISHMENT for its psychological acuity and its devastating dissection of a unique social world under stress.